The role of cities in saving nighttime industry and culture

Just like September 11 marked a before and after in terms of airport and national security, COVID-19 could reshape some of the habits and norms of sociability in large urban areas.While the pandemic still hasn’t reached its peak in many parts of the world, experts already predict that social distancing will be here for a while. As a result, the human endeavour that might change most dramatically is the way we interact and engage with each other.

This crisis has put a test to our capacity to meet others, but it has also created new opportunities to ask important questions about the way leisure and entertainment are distributed in urban areas. When it is over, nightlife and entertainment could play a fundamental role in rebuilding and reconnecting the social systems that have been affected by isolation.

What can cities do to save urban nightlife and protect night-time communities in times of social distancing? How can nightlife transform into a platform for long-term urban recovery? And how helpful can night mayors be in facilitating these relief and recovery projects?

Andreina Seijas, Teaching Fellow and Doctoral Candidate at the Harvard Graduate School of Design, explores the potential of new forms of nocturnal governance to help cities respond proactively to one of the greatest disasters of our time.

The vulnerability of nocturnal industries

Round-the-clock urban activity is an essential feature of the post-industrial city. When services replaced manufacturing as the main sources of economic livelihood, cities realized that there was a competitive advantage in expanding beyond traditional 9-to-5 schedules. This new ethos allowed the nightlife and hospitality industries to flourish, becoming relevant growth engines and significant components of the city as an entertainment and creative machine. While some of these services—particularly the largest ones—were separated through zoning laws into specialized entertainment districts, many others such as restaurants and bars were allowed to inhabit commercial corridors, creating vibrant leisure environments close to residential areas.

In recent years, however, the entertainment machine was losing steam. The rise of online retail, coupled with skyrocketing property costs and gentrification, favoured the disappearance of small businesses and traditional ‘mom and pop’ shops in cities all over the world. Additionally, former industrial and commercial areas became mixed-use communities, where new residents complain of existing nightlife, often putting hospitality venues and creative spaces out of business. In many cases, what helped save independent bookstores, neighbourhood restaurants and local pubs was their ability to promote sociability. Book clubs, trivia nights and other programs helped build a sense of community that favours cooperation with local residents, easing some of the tensions and preventing some of these places from vanishing.

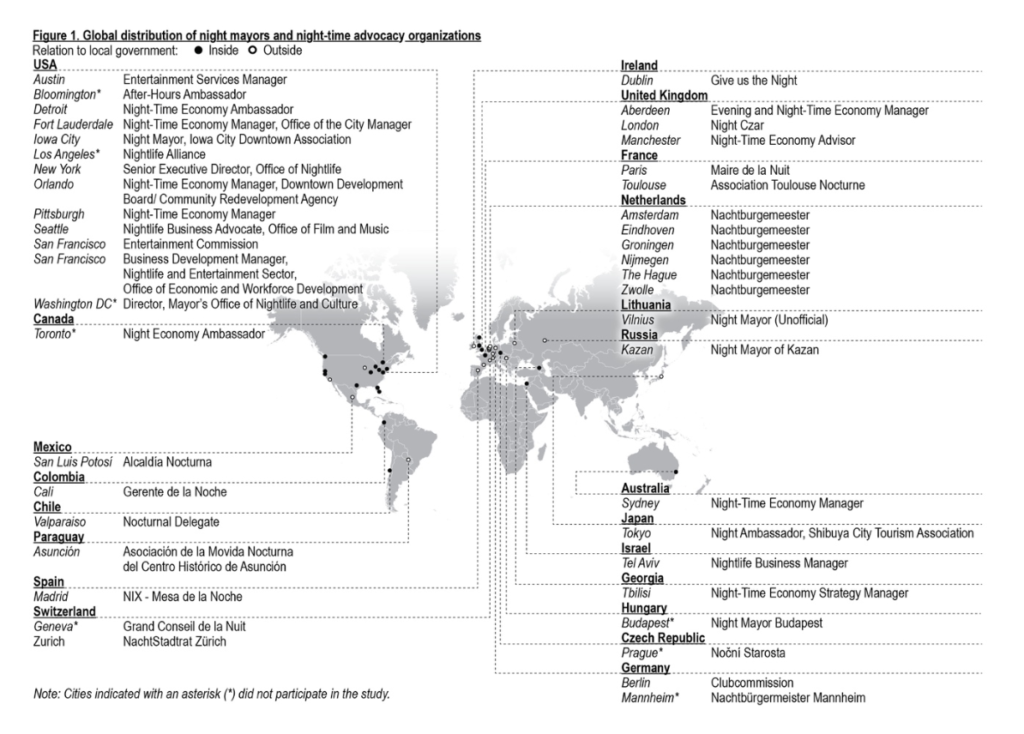

In this context, the world was taken by surprise by the Coronavirus (COVID-19).This invisible yet powerful disease has brought the global economy to a halt, accelerating an urban crisis that was well underway. But way before COVID-19 was declared a pandemic, a new urban actor had already emerged: over the past 15 years, many cities around the world have designated independent advocates or created specialised offices to manage life at night. By early 2020, more than 45 cities had a night mayor or night-time advocacy organisation responsible for mediating between local governments, residents and the nightlife industry. While the urban night has traditionally been a highly contested space, characterised by tensions between creative communities and strict policing and surveillance, these new actors are promoting a new culture of transparency, solidarity and collaboration that calls for integrating—rather than segregating—nightlife and entertainment in urban areas.

In times of crisis, however, government responses tend to be highly reactive and involve severe enforcement measures—such as curfews—that place great pressure on the police and other security forces. While necessary to contain the situation, these responses create an aura of fear and anxiety that affects citizens’ perception of nocturnal environments even months after the lockdown is lifted. In a crisis where crowds are the greatest source of danger, what can cities do to save urban nightlife and protect night-time communities in times of social distancing?

A new era of nocturnal governance

Urban systems of nocturnal governance operate in different levels and range from state actors such as the police, to non-state actors like Business Improvement Districts (BIDs) and nighttime advocacy organisations. A recent addition to the cast of urban actors is the role of “night mayors,” who are independent advocates or specialised government offices responsible for managing nightlife and facilitating its coexistence with other uses in urban areas. While they are still a recent addition, night mayors have already helped raise awareness of the significant contributions that nightlife and hospitality make to cities’ culture and economic development, as well as the need to mediate the conflicts and inequalities that exist in urban night-scapes. These new actors are also helping garner additional resources—both public and private—to manage these issues and creating new spaces for representation that did not exist before.

Aware of the rapid dissemination of this new model around the world, Mirik Milan and I embarked on a project to map it out and understand its variations. The project involved a qualitative study to gather data on the nature, scope, contributions and future perspectives of the role. In the summer of 2018, we distributed this survey and received 35 responses from individuals and organisations in this capacity all over the world. To complement these insights, we also spoke with a group of experts that have been influential in the analysis and propagation of this new urban role: Jim Peters, President of the Responsible Hospitality Institute; Rafael Espinal, former Brooklyn Council Member; Philip Kolvin, former Chair of London’s Night-Time Commission; Charles Landry, urban planner and founder of Comedia Consultancy; Will Straw, professor of Urban Media Studies at McGill University; and Luc Gwiazdzinski, professor and researcher at the Department of Urbanism and Geography at the University of Grenoble.

(Source: Seijas and Gelders, 2020)

Among the results, our study revealed important variations in terms of the place where the role is situated—inside or outside local government—as well as key differences in the scope of the “night mayor” role in European and American cities. While most European night mayors are independent champions, most of their American counterparts have been hired for full-time roles within local administrations. Despite these differences, the study revealed that all night mayors have a strong focus on mediation and that, albeit their limited staff and resources, they are creating new opportunities to promote safer and more inclusive night scenes through experimentation. In recent years, cities like Amsterdam and New York have tested new partnerships to de-escalate night-time crime and nuisance through mediation, while others like Orlando are trialing new ways in which ride-hailing operators and city authorities can jointly design efficient strategies to manage crowds in highly saturated nightlife districts.

Nightlife and hospitality are among the most affected by social distancing policies as these industries rely heavily on crowds and group gatherings. Following massive closures, strict curfews and the cancellation of events from the 50th anniversary of Glastonbury to the Summer Olympics in Tokyo, what can cities do to lessen the impact of this crisis over already vulnerable night scenes?

Different responses to the same crisis

Global reactions to COVID-19 have been wide-ranging. Similar to strategies to manage climate change, most responses seek to either contain the spread of the virus (mitigation) or adapt basic human functions such as working, shopping, studying or socializing to the new social distancing regulations (adaptation). When it comes to adapting nightlife to these regulations, three phases can be identified.

- The first phase is containment, which involves immediate measures ranging from reducing venue capacity, to imposing a curfew, to declaring a lockdown.

- The second phase is relief, which involves solutions to moderate the short-term impact of the crisis such as tax, rent and utility freezes for business owners, as well as fundraising efforts such as United We Stream—a live stream fundraising campaign created by Berlin’s Clubcommission and implemented in other cities like Manchester and Vienna since early April.

- The third phase of managing the nightlife crisis refers to recovery, or the tools that cities can develop to enable a speedy rehabilitation of freelancers, musicians, performers and many others once social distancing comes to an end. This includes resources such as online surveys implemented by cities like Philadelphia, New York and Los Angeles to gather key data on the number of people and organisations affected by the closures to contain the disease, in order to then lobby local governments for assistance.

While our study on nocturnal governance revealed important differences based on where night mayors are situated (inside or outside local government), these differences seem to become less relevant in the context of a global pandemic. Crisis management demands the participation of all kinds of nocturnal actors—from private to public, from official to unofficial. While containment demands a more top down response, community outreach becomes more relevant during the relief phase as social networks can be more necessary than the police to mobilise resources in a timely manner. Finally, the amount of resources and coordination necessary for recovery will require significant multi-stakeholder collaboration. In this context, night mayors’ convening power, vast social networks and their capacity to bridge the gap between sectors such as nightlife industries and local authorities, provide a unique platform to design and implement creative relief and recovery solutions to manage some of the impacts of this ongoing crisis.

The future of nightlife after social distancing

Density and nightlife often go hand in hand. In post-industrial cities, nightlife became an industry in its own right, benefitting from large agglomerations of consumers that demand exciting and diverse amenities, allowing them to specialise. This partly explains why the night-time economy in places like New York, London, Tokyo—and even Las Vegas—is an important tourist attraction as well as the source of millions of jobs. However, in a world where the norm is to keep at least 6 feet away from each other, its “sidewalk ballet” and incessant variety of human scale interactions are the reason why the Big Apple is the U.S. epicentre of the pandemic.

Just like September 11 marked a before and after in terms of security, COVID-19 could reshape some of the habits and norms of sociability in large urban areas. This crisis has already allowed many of us to realise that working from home is not only a feasible option, but also a convenient alternative to long commutes that take a toll in the environment and on our personal relationships. It has also encouraged those of us who teach to think more creatively on how to use technology to democratise access to quality education. But perhaps the human endeavour that will change more dramatically is the way we interact and engage with each other.

This crisis has put a test to our capacity to meet others, but it has also created new opportunities to ask important questions about the way leisure and entertainment are distributed in urban areas. When this crisis is over, nightlife and entertainment could play a fundamental role in rebuilding and reconnecting the social systems that have been affected by isolation. But, how will the nature of these activities change in order to meet new demands?

One possibility is to rethink the relationship between nightlife and density. While nocturnal vibrancy is often measured in terms of foot traffic, the number of restaurants per capita, or the number of people that occupy a public space at a given time, the truth is that we don’t need to be packed like sardines into a bar or a restaurant to experience quality nightlife. The question is, how dense should nocturnal environments be? Decentralising amenities such as nightlife, leisure centres and creative spaces could help create medium-intensity entertainment hubs rather than congested city centres, where tensions between residents and revelers tend to exacerbate. This requires strategic planning, design and sound regulations to manage both social and environmental impacts, as well as empowering new local champions willing to guide these communities.

A second possibility is to rethink the notion of licensing. Just like fine dining restaurants have rehashed their business model and are delivering burgers and cocktails to survive the current crisis, these unprecedented circumstances might finally make cities realise that the strict separation of uses—live, work, play—is no longer feasible in urban settings. Zoning and licensing are regulatory straight-jackets for those seeking to innovate, particularly in the creative and cultural industries. While they are recognised as harmful practices, many restrictions remain in place in order to reduce externalities—such as sound—associated with nightlife and entertainment. In cities such as San Francisco, nightlife advocates such as the city’s Entertainment Commission have been instrumental in creating new procedures to determine the compatibility of new residential developments with existing nightlife uses. More flexible regulations and procedures can also enable temporary uses, ghost kitchens and other hybrid ventures—such as co-working spaces that double as leisure centres—that can help keep streets active and vibrant throughout the day.

A third possibility is to rethink the notion of closing hours. Most cities around the world have operating hour restrictions in place, often linked to alcohol sales and consumption. In order to offset some of the impacts of this crisis, some cities could grant businesses the possibility to open later as a tactic to help nightlife and cultural scenes bounce back. Before doing that, however, cities will need to conduct feasibility studies or even randomised trials to determine which neighbourhoods are more suitable to have extended hours based on factors such as safe and equitable access not only for patrons, but also for those who work at night. Pandemics can be democratising experiences as we are all affected in the same way. Hopefully they will encourage us to rethink more carefully about the way we structure labor conditions for night- shift workers and other vulnerable populations, and create more tolerant and inclusive night spaces.

Flexibility in licensing and closing hours has allowed places like Berlin and Amsterdam to innovate. While Berlin hasn’t had a curfew since 1949, Amsterdam has been granting 24-hour licenses to decentralise nightlife since 2012. It is not a coincidence that these two European cities have some of the most creative night scenes in the world, and also that they were the first to create night mayors and night-time advocacy organisations. While all countries face different levels of preparedness, they can all benefit from sharing resources and information. From this perspective, this new global network of nightlife advocates is a unique example of solidarity and collaboration in times of crisis.

As the following weeks unfold, we will see which of these possibilities materialise and which cities are more successful in protecting their night scenes. What is certain is that those cities that have a nocturnal governance system in place—under any of its variations—already have a competitive advantage to respond proactively to one of the greatest disasters of our time.